James Spain was a 22-year-old Dubliner and member of the anti-Treaty IRA when he was shot dead by the Free State Army in November 1922. The killing took place in the area then known as Tenters Field off Donore Avenue, only minutes away from where Spain grew up. There is no plaque or monument to mark the spot of this incident. We have previously covered Noel Lemass and William Graham.

James was born in December 1900 to Francis and Christina Spain, both originally from Dublin.

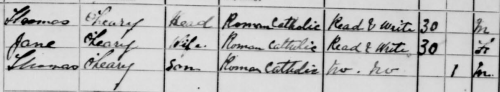

The 1901 census shows that the family were living at 63 Harty Place off Clanbrassil Street Lower. Francis (30) was a boot maker while his wife Christinia (24) looked after their three sons – Joseph (4) Francis Jr. (2) and James (4 months). All were Roman Catholic.

Ten years later the family had moved to 9 Geraldine Square off Donore Avenue. The 1911 census tells us that Francis (41), still a boot maker, and his wife Christina (35) were now living with their six sons and one daughter. These being Joseph (14), Francis Jr. (12), James (10), Annie (7) who were all at school along with Michael (5), John (3) and Patrick (1). Francis had Christina had been married for fifteen years.

At the time of his death in 1922, James Spain was listed as a upholster living at 9 Geraldine Square which corresponds with the census records. Relatives told the subsequent inquest that he had escaped from a military prison three weeks previously. His grave states that he was 1st lieutenant of A Company, 1st Batt. of the Dublin Brigade IRA.

Spain was a part of a 20-30 strong IRA team who launched a major military attack on Wellington Barracks (now Griffith Barracks) on the night of 8 November 1922. The principal attack was delivered at the rear of the barracks while shots were also fired from house-tops in the South Circular Road area.

The Irish Times, the following day, reported that the neighborhood was the:

” scene of a miniature battle. Thompson and Lewis guns answered each other with equal vigour, the sounds of the firing being heard all over the city … For nearly an hour ambulances were busy taking the wounded to hospital.

A total of 18 soldiers were hit. One was killed instantly and 17 were badly injured.

Republicans like Spain tried their best to flea the area and escape arrest. John Dorney writing in The Irish Story summarised that:

The Republicans made their escape across country, through the villages of Kimmage and Crumlin, pursued by Free State troops. They were seen carrying two badly wounded men of their own.

Spain ran north, possibly out of instinct, towards the Donore Avenue area and his home. Witnesses claim that he was dragged out of a house by soldiers and shot in Tenter Fields while the Army’s official version of events claim that he was shot in the Fields after he refused an order to stop running.

The Irish Times of 10 November 1922 reported on the events leading up to his death. Two hours after the attack on the barracks, Spain ran up to 22 Donore Road. Here a woman, Mrs. Doleman, was feeding her birds in the yard. He shouted “for god’s sake, let me in” and fell just as he got inside the gate but managed to make it the kitchen where he collapsed onto a sofa. According to Dolenan, he was only there for a few minutes before a group of Free State soldiers ran into the house and grabbed Spain. Mrs. Doleman heard shots a few minutes after.

Map showing Geraldine Sq. in the top left hand corner (where Spain was grew up), Tenters Field (where Spain was shot) and Susan Terrace beside it (where his body was found)

As often in these cases, this is where the story diverges slightly.

At the inquest, an unnamed member of the Free State Army reported that himself and five riflemen in a Lancia car came across one of the attackers (Spain) in Tenter Fields and “called on him to halt four or five times”. After this request was denied, they shot him and the man fell.

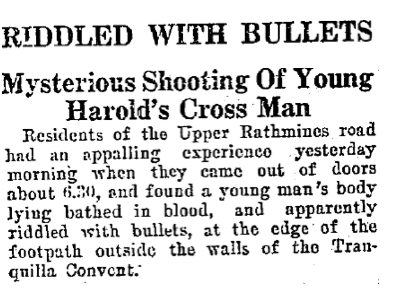

Either way, the body of this young 22 year old local was found at No. 7Susan Terrace at the edge of Tenter Fields. He had been shot five times.

The Irish Independent on 11 November 1922 wrote:

The remains of Mr. James Spain … were last night removed from the Meath Hospital to the Carmelite Church, Whitefriar St. A man who was introduced at a previous protest meeting as Mr. O’Shea of Tipperary mounted the ruins in O’Connell St. last night and addressing those about him, asked that the meeting of protest against the treatment of prisoners be adjourned as a mark respect to the late Mr. Spain.

Two days later, the same newspaper reported on the funeral:

A number of the Cumann na mBan marched behind the hearse and there was a large cortege. The remains were received in the mortuary chapel by Rev. J. Fitzgibbon. A large numbers of wreaths were placed on the grave and three volleys from firearms were fired over the grave. The chief mourners were – Mr. F. Spain (father), Mrs. Spain (mother), Joe, Frank, Mickie, Jack, Paddy and Peadar (brothers), Annie, Molly and Crissie (sisters), Maggie and Mickie Spain (cousins), Annie and Mary Spain (aunts) and Jack Spain (uncle)

Spain was buried in the family plot in Glasnevin. Thanks to Shane Mac Thomais (of the Glasnevin Museum) for getting in touch and sending me the image of the grave.

James Spain was just one of dozens of young anti-Treaty IRA men who were killed by the Free State in Dublin from August 1922 to August 1923. Of the 26 murders as far as I can work out, 16 are marked by small monuments where the bodies were found.

If you have anymore information about James Spain, please get in touch by leaving a comment or emailing me at matchgrams(at)gmail.com